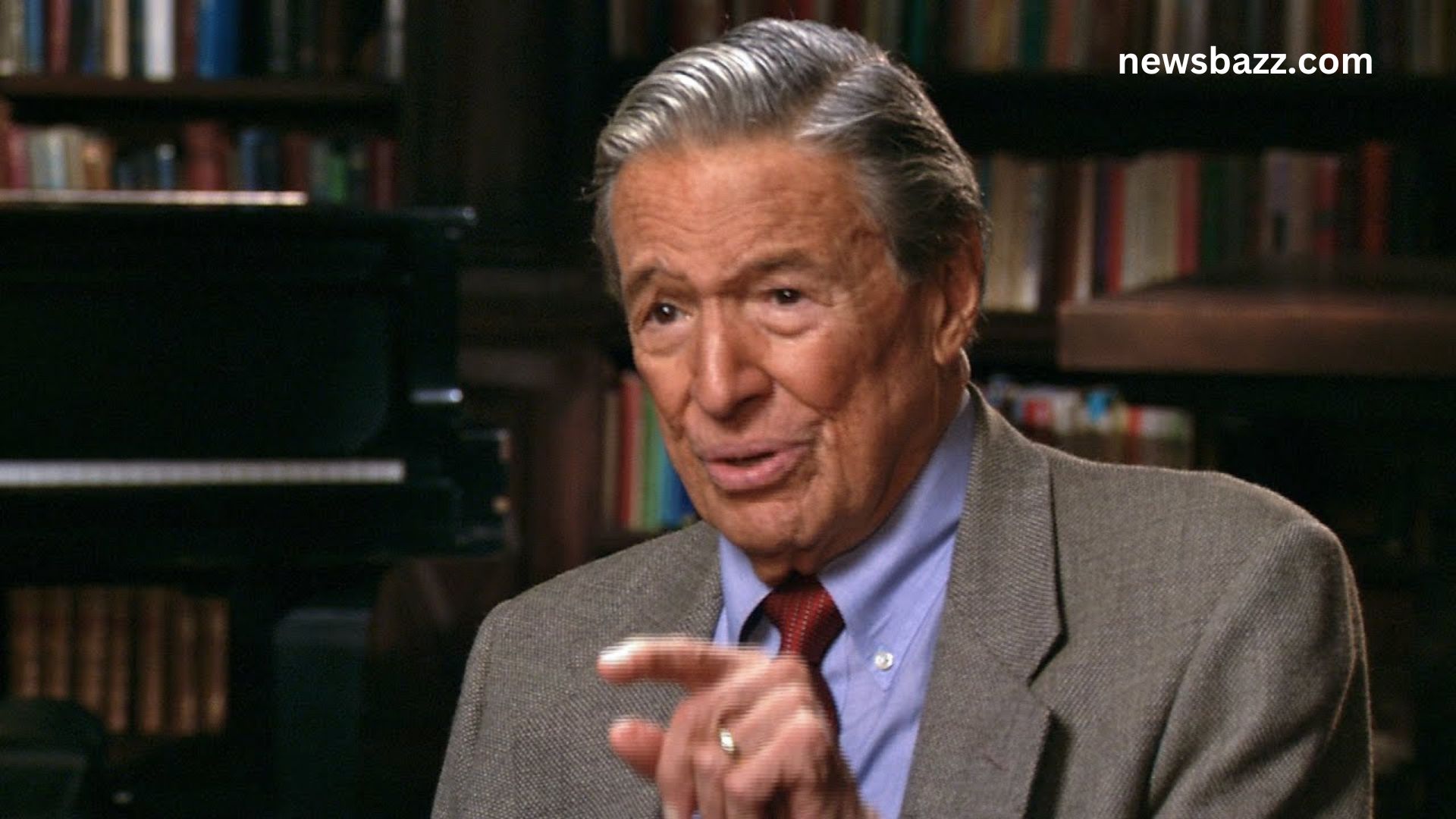

From his first interview on the small screen in New York to his final appearance on 60 Minutes, Mike Wallace was the icon of a responsible and thorough era of television journalism. His screen presence—that stony glare, the bemused eyebrow-lift and the gleam in his eye that presaged a knockout follow-up question—was iconic.

Mike Wallace’s Life

Mike Wallace was born in Brookline, Massachusetts to Russian Jewish parents in 1918. He appeared in front of early monochrome cameras as a radio actor, narrator of soaps and serial dramas, host of game shows and other entertainment programs, TV commercial spokesman for everything from shortening to Parliament cigarettes.

During World War II, Wallace served as a communications officer on the USS Anthedon submarine tender. Though he saw no combat, he traveled to Hawaii, Australia and Subic Bay in the Philippines. After the war he worked on a variety of radio and television shows, including the detective drama ‘The Crime Files of Flamond’ and the syndicated game show ‘Info Please.’

By the late 1950s, he had shifted his focus to interviewing, appearing on local New York TV’s Night Beat and later the nationally broadcast ‘CBS News Sunday Morning.’

Over the course of his career, Wallace won 21 Emmy Awards. He also received three George Foster Peabody awards, three Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University awards and was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania.

A renowned tough interviewer, Wallace sat down with deposed Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. He was also a proponent of hidden-camera exposes and ambush interviews. At times, his own abrasive demeanor and penchant for confrontation made him a bigger story than the people he interviewed.

Mike Wallace’s Career

From his early days interviewing local New York personalities on the smoke-wreathed television show Night Beat to his years as lead reporter for 60 Minutes, Mike Wallace was a hard-boiled reporter who rarely cut his subjects much slack. His brusque style was often effective, and it was usually matched by an ability to dig out the most honest responses from his subjects. Wallace was a talented performer in his own right, and his TV screen presence—that prosecutor’s glare, the bemused eyebrow-lift, the gleam that presaged a knockout follow-up question—was an essential element of his success.

His interviews were often groundbreaking, and he was particularly adept at exploring the political cross-currents of mid-century America. In an interview with Ayn Rand on the eve of Atlas Shrugged’s publication, for example, Wallace nailed the book’s themes of individualism and self-determination.

There were missteps, of course, especially when Wallace went too far with his showmanship. His 1982 CBS Reports special, “The Uncounted Enemy,” accused General William Westmoreland of over-counting enemy dead in Vietnam and landed him in a libel suit with the Army Corps of Engineers.

Despite these and other scandals, however, Wallace was widely seen as an emblem of a more responsible era of news reporting. He died a respected journalist, though his reputation didn’t fully recover from the scandals that dogged him throughout his career.

Mike Wallace’s Personal Life

Mike Wallace has devoted his life to unpacking the essential lessons from centuries of American history. He’s a Distinguished Professor of History at John Jay College and the CUNY Graduate Center. He’s also the founder of or cofounder of several influential historical projects, including the Radical History Forum and the Gotham Center for New York City History.

After graduating from the University of Michigan, Wallace worked in radio broadcasting, first in Grand Rapids, then Detroit and Chicago. In 1951, CBS executives noticed him and lured him to New York City. He made the transition to television and diversified his skills by hosting daytime shows, starring in dramatic roles in the prestigious anthology Studio One, and even portrayed a barker in a children’s show called Super Circus.

As a correspondent, Wallace traveled widely to cover events such as the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign. In 1969, he turned down a job on Nixon’s campaign staff to join veteran CBS news producer Don Hewitt in creating a primetime magazine show, 60 Minutes. He was a full-time correspondent with the program until 2006.

Among his many honors, Wallace won 21 Emmy Awards, three Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Awards, five George Foster Peabody Awards and a Paul White Award. He also received a Distinguished Achievement Award from the University of Southern California School of Journalism and a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award.

Mike Wallace’s Interviews

Mike Wallace’s interviewing skills set him apart from the rest. His probing questions and hawk-like attentiveness changed television news for the better. He would be known as television’s grand inquisitor, but he never became a bully. He was “smart and fair” but was also willing to call BS on his subjects. He was also a gifted storyteller who could draw viewers in.

As a daytime host of quiz shows and game shows, Wallace honed his skills for interviewing, but his real breakthrough came when he joined the staff at CBS Television in New York City. He starred with his wife Buff in a popular variety show called All Around the Town. They traveled to New York’s hot spots like Coney Island, the ballet and restaurants and informally interviewed promoters, performers and patrons.

Wallace’s interviews with the likes of baseball player Jose Canseco and euthanasia advocate Jack Kevorkian blew open their respective scandals. He won 21 Emmy awards during his career.

Tragedy, however, would change Wallace’s life and focus. His oldest son, Peter, died in a hiking accident in Greece. This prompted Wallace to quit his commercial work and concentrate on what had always been his passion: journalism. He became a correspondent for 60 Minutes, and the interviews that followed made him famous. He was also a vocal critic of corporate censorship in the 1990s when he confronted cigarette executives over their refusal to disclose the addictive nature of nicotine.